andrew w. moore | travel | Northern Spain, 2025

Bilbao is the de facto capital of the Basque Country (Euskal Herria [Euskara], Pais Vasco [Spanish]). Boise is home to the largest Basque diaspora outside of Spain, and the city hosts Jaialdi, a Basque cultural festival, roughly every 5 years since 1987 (although this was disrupted by the 2020 pandemic). We visit downtown's Basque block almost every week, but Jenny and I were excited to visit the region for ourselves.

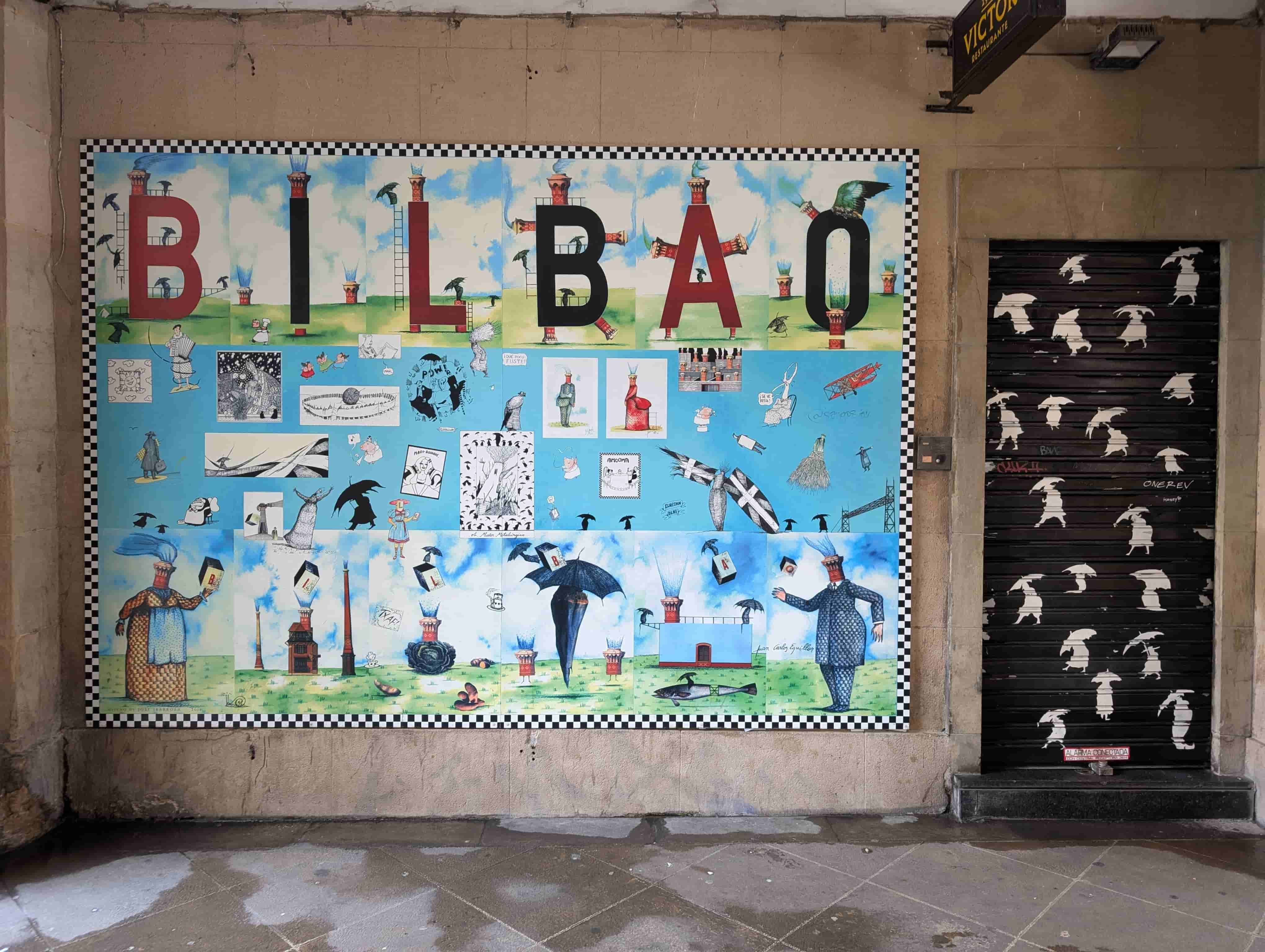

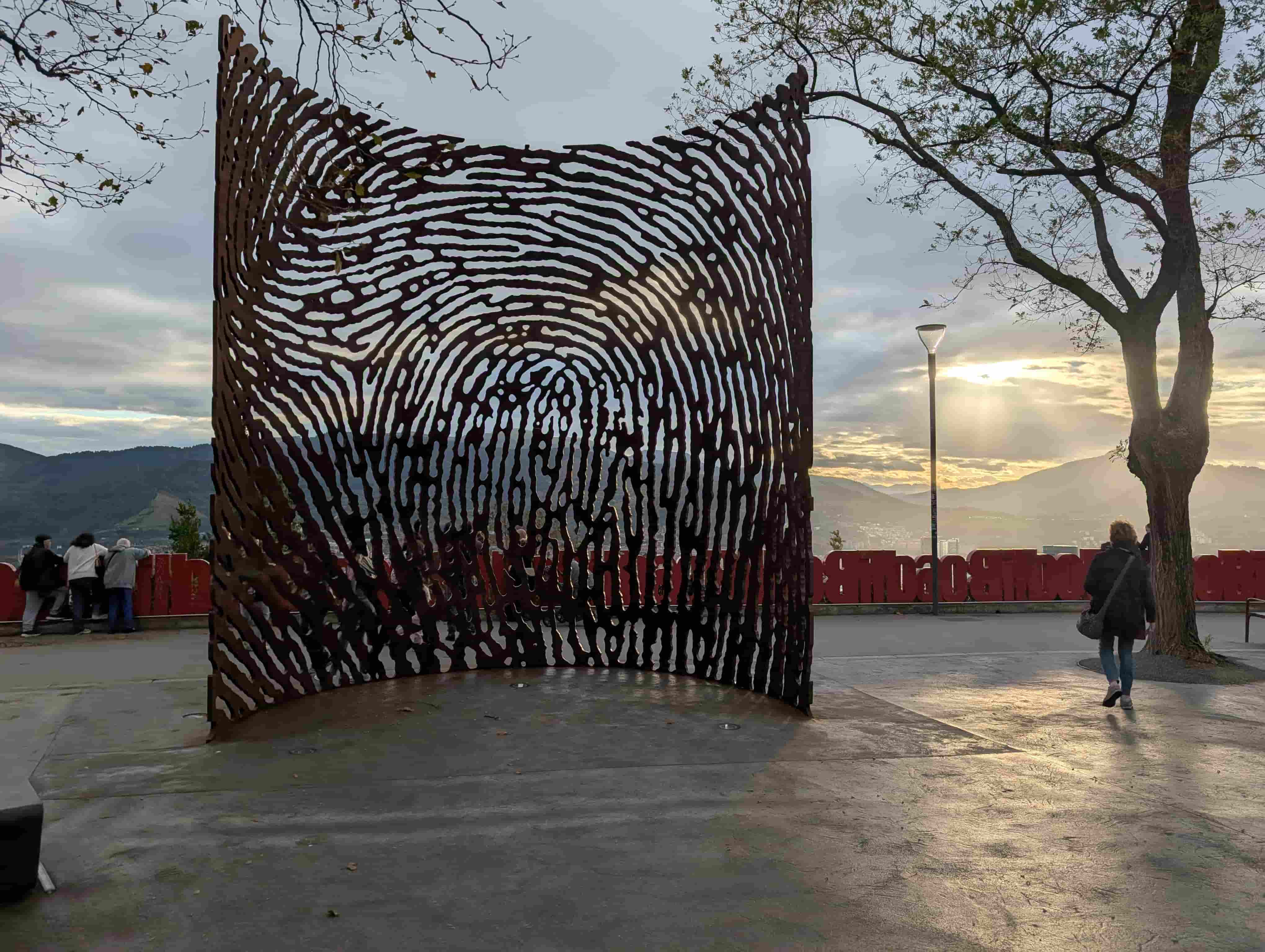

Jenny and I stayed in Casco Viejo, the city's old-town. We were a scant minute or so from Plaza Nueva, an excellent spot to find pinxtos and enjoy a midday vermut. The neigborhood is distinctively visible from the Artxanda viewpoint, due to its shorter buildings and slimmer streets compared to the rest of the city. Overall, we enjoyed how walkable Bilbao was. The city's riverbanks have been reclaimed over the past 3 decades, converting warehouses and staging areas to pleasant public spaces.

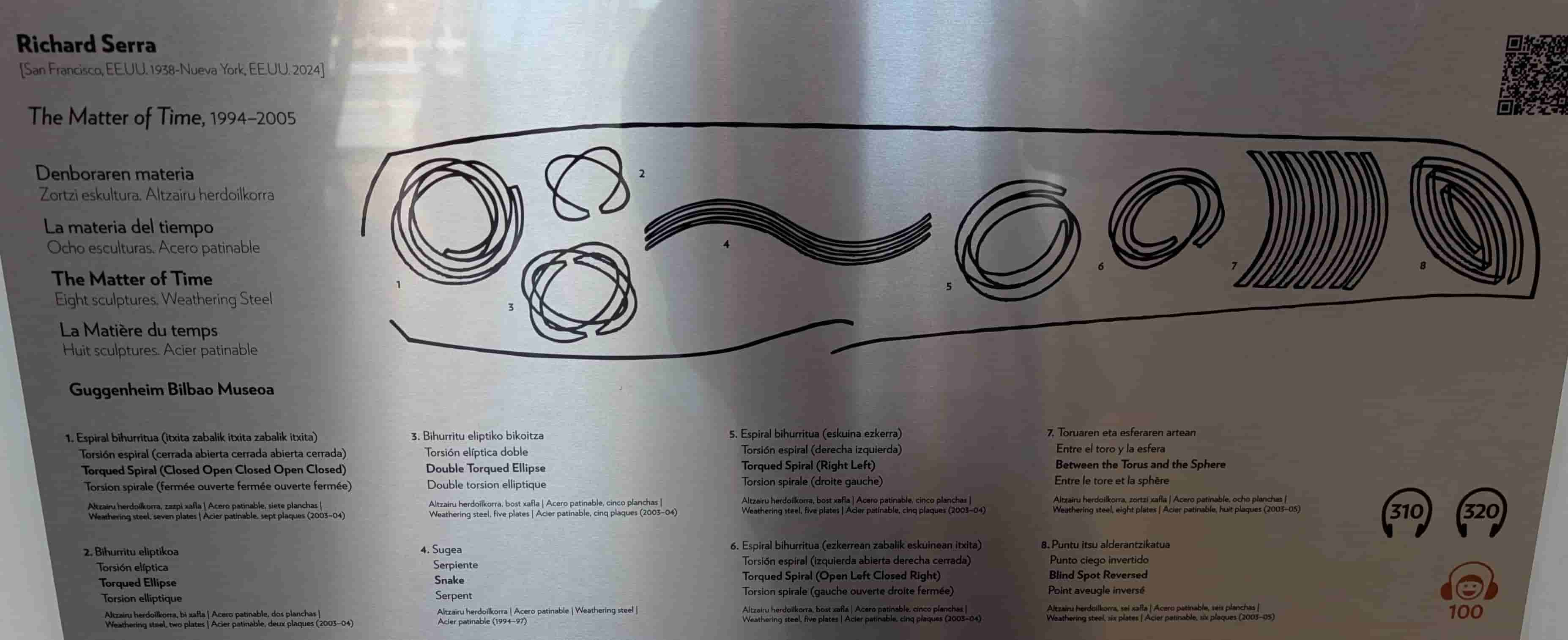

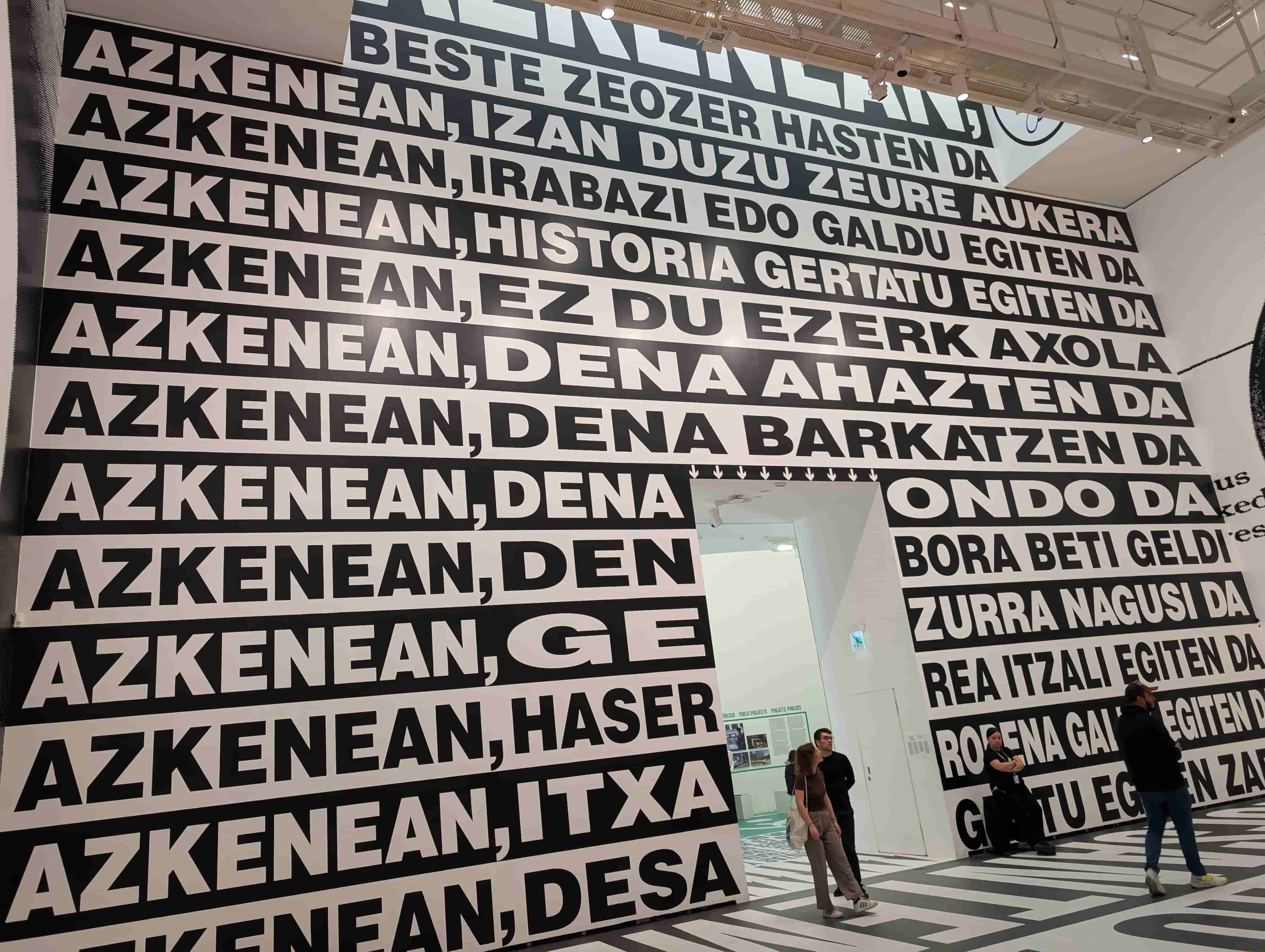

The Guggenheim Museum

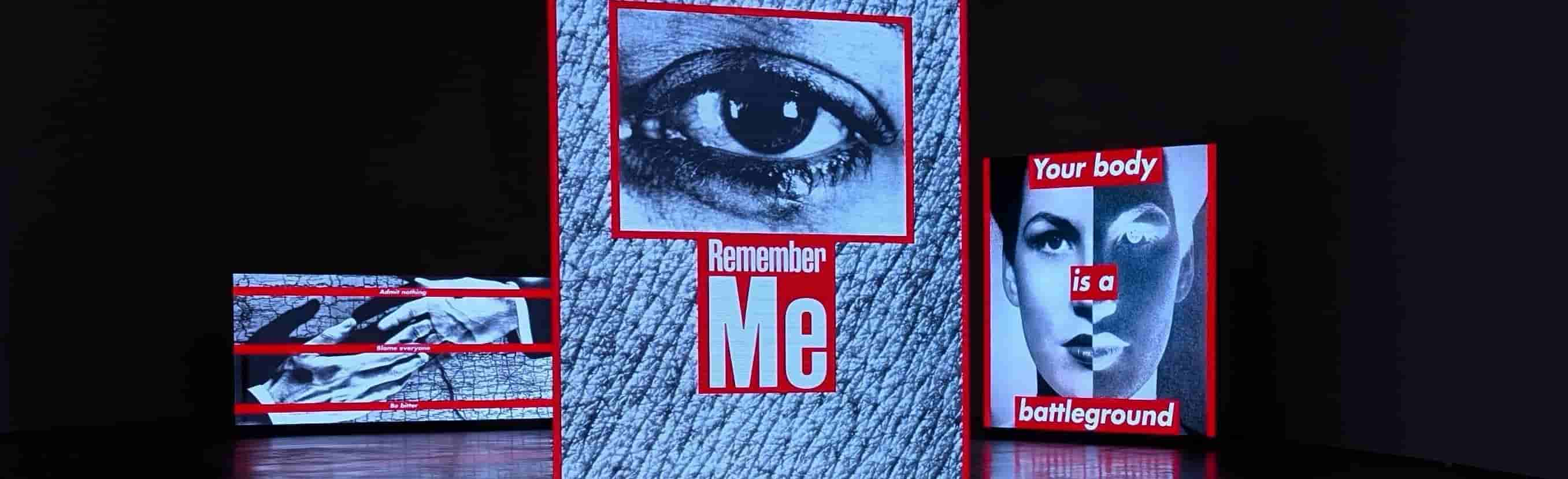

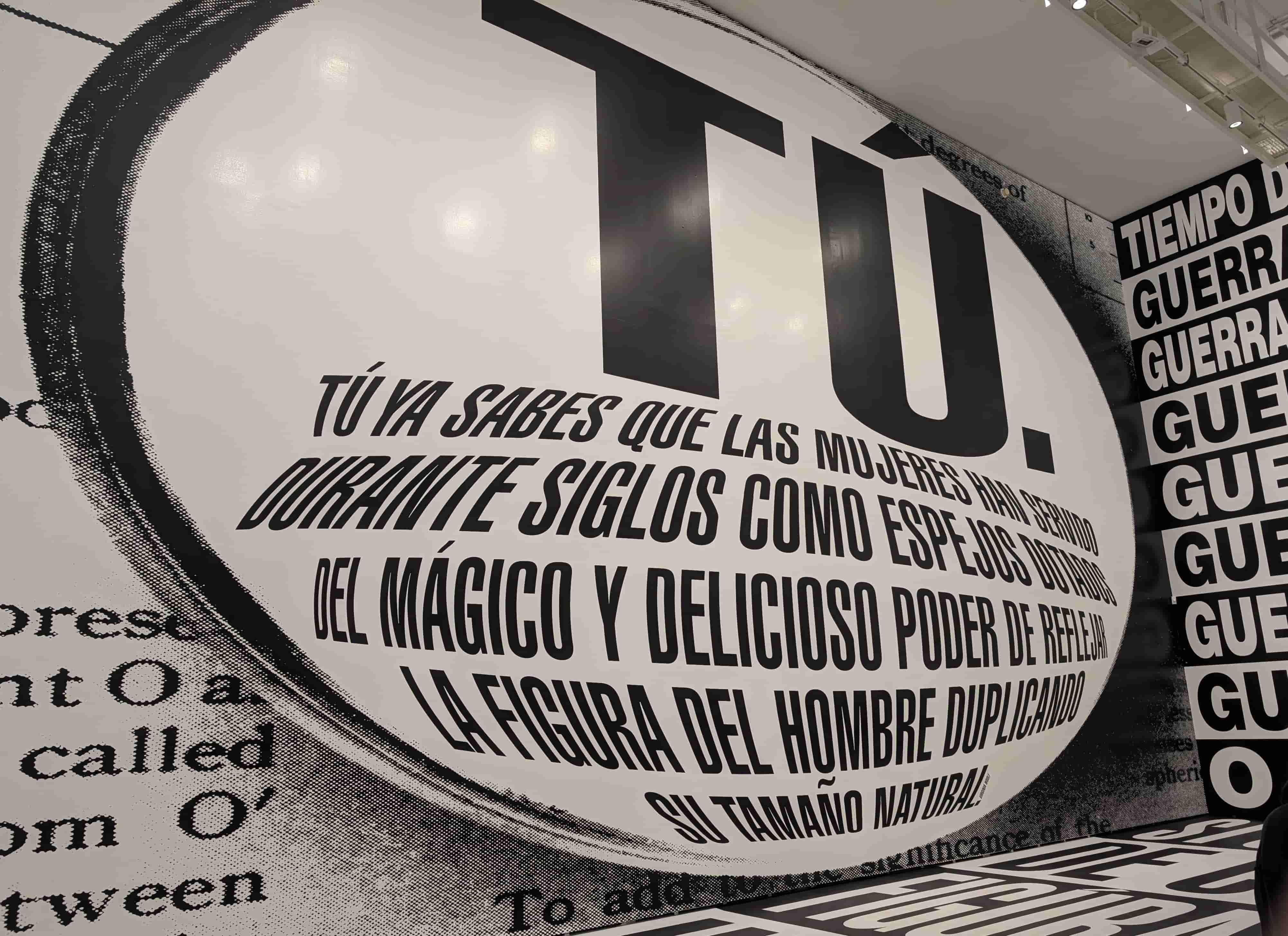

Bilbao has undergone a transformation away from its long-running industrial history. During the 80s and through the late 90s, the shipbuilding and mining industries that had previously sustained the city were fading. Some bombings carried out by the ETA (a Basque separatist group) were done to protest the opening of the Guggenheim itself. Today, the Guggenheim is a symbol for how Bilbao has reinvented itself, and become an international destination. Directly and indirectly, the museum produces about €400M for the city each year. The museum almost felt smaller inside than I expected. Its second floor was hosting an exhibition from American artist Barbara Kruger, titled "Another day. Another night."

Gaztelugatxe, Mundaka, Gernika-Lumo

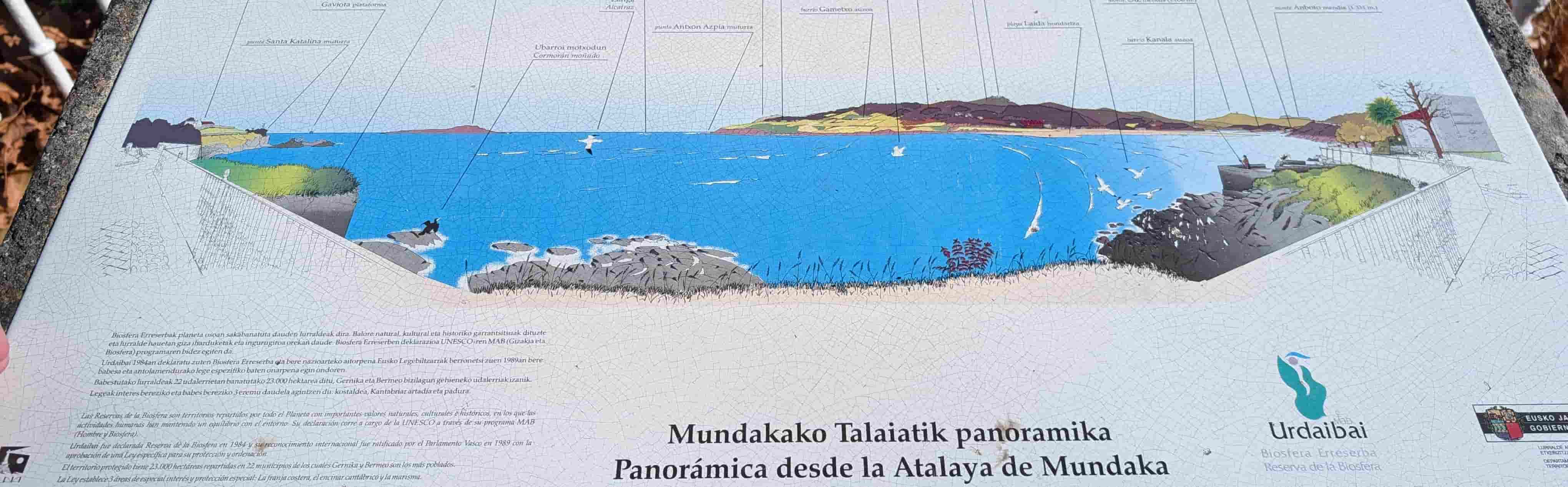

On our second day, we booked a tour that got us outside Bilbao. Our guide, a local named Asier, took us to a local landmark called Gaztelugatxe (famous as a set for Game of Thrones), a fishing village called Mundaka, and the small city of Gernika-Lumo. Jenny and I haven't watched Game of Thrones, but the trail up to the church of San Juan on Gaztelugatxe provided some incredible views. Unfortunately, due to the show's popularity, the peninsula suffers from overcrowding during peak seasons. Similar to our experiences visiting Japan, there's ambivalence from residents about the impact of tourism. On one hand, visitation stimulates conservation efforts and provides economic benefits, but these efforts are calibrated in part by the gaze and desires of tourists. It was hard to avoid thinking about this during our drive along the tiny mountain roads leading to Gaztelugatxe.

I was quite struck by our visit to Gernika-Lumo. The town is home to the Gernikako Arbola ("tree of Gernika"), whose ancestors were a traditional meeting place for the region's representative assemblies during the middle ages. The tree is considered a symbol of the Basque people's tradition of self-governance, formalized as laws called fueros. The fueros are recognized as having influenced John Adams (and the subsequent drafting of the US constitution), who wrote about them during his trip to Europe in 1780, in which he passed through Bilbao.

However, most people outside the Basque Country probably know of the city due to Picasso's famous painting, Guernica. The mural depicts the bombing of the town during April 1937, conducted by Nazi Germany's Condor Legion. Nominally, the bombing was meant to impede the retreat of Republican forces on the front east of Gernika. Specifically, bridges and roads were key targets, if you accept this view. However, the Luftwaffe used incendiary bombs, setting fires that burned for several days. This isn't easily reconciled with claims that the bombing was tactical. Ultimately, something like 75% of the city was destroyed as a result of the attack. In the aftermath, Nationalists propagated lies that communists (rojos) had intentionally set fire to the city, and that no one actually died during the events. Nationalist forces occupied the city 3 days after the bombing, seizing records and preventing the local government from properly determining the number of casualties from the attack.

Its circumstances are unique, but my sense is that Gernika-Lumo (and the Basque Country more generally) understands itself as part of a broader community of survivors of excessive and industrialized violence. The city has been working to preserve the historical memory of what happened, via the recording of oral accounts from survivors, and archiving photography from before and after the bombing. A sapling from the Ginkgo tree that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima has been planted in a park south of the "Guernica" mural. While the particulars differ greatly, I believe this broader historical understanding is why we saw so many expressions of solidarity with the Palestinian people throughout the region. It's almost inconspicuous in the photo above, but the idea of a Palestinian flag being displayed on a city hall in the US is nearly inconceivable.

Lastly, here are a few additional things we learned about the Basque country:

- The Basque language, Euskara, is a language isolate. It might use some Spanish loanwords, but is linguistically unrelated to other languages in Europe. The language was banned during Franco's regime (people could be fined for speaking the language in public). After Spain returned to democratic governance, the region was able to (re)establish Euskara as an official language, alongside Spanish. Our guide, Asier, told us that 75% of secondary school students take their finishing exams in Euskara. I haven't been able to find statistics on this exact claim, but I did find reporting that roughly 75% of those aged between 16-24 in the Basque Autonomous Community speak the language.

- 94% of tax revenue collected within the Basque Country remains within the region. This was established as part of Spain's entry to the European Union, and echoes the ancient "Basque Privileges" (fueros). Asier speculated that this may partially explain why the trajectory of the Basque Country has differed from Catalonia (another region with an independence movement).

- Support for an independent Basque country is fairly low; it reached highs of around 40% in 2021/2022, but appears to have dropped to around 19% (as of November 2024).

Pinxtos ("pinch-o", Spanish pinchar, "puncture")

Turning to much lighter subjects, Pinxtos are a lovely feature of northern dining. Rather than going out for tapas, the Basques have pinxto potelo, the act of hopping between bars to try different pinxtos. Pinxtos are bar snacks, so they might seem reminiscent to tapas, but they differ from tapas in a few ways:

- Pinxtos are always standalone items, rather than a small portion of a larger dish. Instead of getting a slice of tortilla or a plate of paella, you're more likely to get a small bun or sandwich.

- Many pinxtos include a wooden skewer (pinchar). A classic pinxto is the "Gilda": a skewered trio of an olive, anchovie, and pickled banana pepper. These are super tasty, perfectly paired with a zurito (a half-pint from the bar's tap).

- Pinxtos almost always include bread, which is usually standard Spanish pan. However, we also saw restaurants experimenting with bao buns.

- The best thing we tried was probably the set of pinxtos in the bottom right. This was a caramelized apple with pulled duck, and a cup of fried swordfish (with a creamy sauce) and thinly sliced onions. Paired surprisingly well with Vermut Preparativo (sweet vermouth mixed with a bit of Campari over ice).

Metrics

We were on our feet for a bunch of this trip! Here's some of the stats I logged on my watch each day. During this segment, we averaged about 13,317 steps per day.